...we all must sing

"Impossibility, like Wine / Exhilarates the Man/ Who tastes it"

(Emily Dickinson)

Showing posts with label whiskey. Show all posts

Showing posts with label whiskey. Show all posts

Saturday, May 17, 2014

Sunday, May 4, 2014

Of Manly Tables and Girly Drinks

Two quick follow-ups to my last post on gender and drinking.

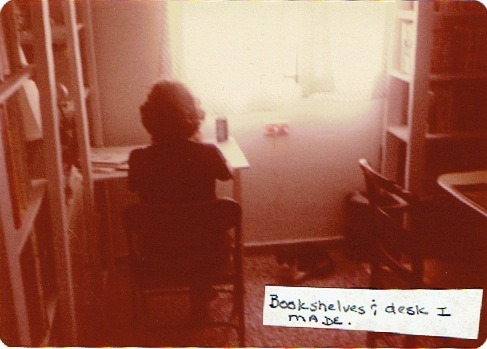

First, on the manliness of making tables:

Both Whiskey Catholic and the Woodford Reserve bourbon commercials I mentioned last week suggest that making furniture (a table for the former, a bookshelf for the latter) is a hallmark of manliness.

For the record, I love hand-made furniture. Growing up, all the activity in my house swirled around a large, rustic wooden kitchen table. That table was made by hand. By my mom. When she was pregnant with me.

Apparently, she also made a bookshelf. And a desk.

Another note:

Katy Waldman, building on this post by Lisa Wade, asks about the flipside of manly drinking: girly drinks.

Waldman makes a couple of great points that further highlight the absurdity of gendered drinking. First, in considering the notion that drinking whiskey is considered “manly” because it involves proving yourself by drinking the hard stuff, she observes, “Other types of self-punishing willpower—the feminized kinds—only attract scorn.” Whiskey is manly because it’s “hard,” but vodka is feminine because… why?

Waldman and Wade also point out that women who transgress gender norms in drink-ordering—who order whiskey at a bar—can be treated as something special. But this isn’t really challenging gender norms, just reinforcing the idea that male-associated drinks are better and more worthy. In ordering whiskey, these girls mark themselves as “cool girls,” setting themselves apart from the other, less cool women who drink, I don’t know, wine coolers.

Waldman writes:

Wade makes a smart observation, which is that while bartenders and waitstaff oftenexpect their female customers to order “juicy or sweet” beverages, those who defy convention with a whiskey neat get vaulted to cool-girl glory. “This is typical for America today,” she writes. “Women are expected to perform femininity, but when they perform masculinity, they are admired and rewarded.”She’s right. I can still feel the heat shimmer of your judgment, reader. And the side-eye I’m likely to get, asking a waiter for something “refreshing” or “light” (or, God forbid, “bubbly”) is compounded by the approval my female friends draw just by opting for “one of your darker beers, please.” A girl who handles her liquor—and what a weird verb, handle, as if recreational drinking were some kind of beast to manage—seems “down,” chill, hot. She’s almost one of the guys, and in that wordalmost dwell all the mysteries of sex appeal us Schnapps-sucking chicks will never understand.

It seems to me that the healthiest attitude towards gender and drinking is the one expressed by a bartender Waldman quotes, who tells her “But honestly, the women bartenders I work with tend to be a lot less opinionated about this stuff than my male friends. We respect each other’s right to go order a martini and then an old fashioned.”

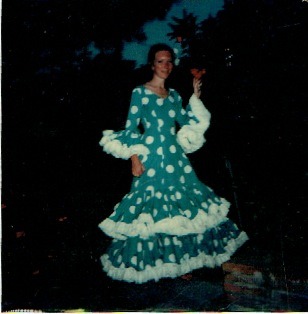

If you like it, drink it. Come to think about it, that was kind of my mom’s approach to crafts: she made the flamenco dress below (she was living in Spain at the time) and she made a table. I don’t think she gave much thought to what either activity said about her gender identity. If she wanted it, and could make it, why not do it?

Tuesday, April 29, 2014

The Catholic Church's Real Drinking Problem

Over at the New Yorker, Ian Crouch critiques the Woodford Reserve commercial that ran during the season premiere of AMC’s Mad Men. In that ad, a woman’s voice tells us:

When I see a man drinking bourbon,

I expect him to be the kind who could build me a bookshelf.

But not in the way that one builds a ready-made bookshelf.

He will already know where the lumberyard is.

He’ll get the right amount of wood without having to do math.

He’ll let me use the saw,

and not find it cute that I don’t know how to use the saw.

For Crouch, this represents “a rather old-fashioned statement about gender.” Crouch goes on:

Despite the modern, fashionable feel of its new ads, Woodford Reserve’s definitions of gender are radically narrow, and its sense of the possibilities for human sexuality even narrower. Men must appeal to women, and women to men. To attract women, men have to be rugged and capable while maintaining a perfect veneer of nonchalance. Women can spot a phony or a wimp a mile away. Women, meanwhile, have to be forever good sports, proud of their men’s rough edges and presentable in mixed company with the rowdy boys. The core message is one of stern-faced seriousness: Bourbon defines a man’s world, and women are welcome only if they play by the men’s rules.

For the record, the Woodford spot didn’t really bother me. Even Crouch concedes that “[i]n the pantheon of sexist advertising, Woodford barely merits inclusion.” But the conversation reminded me of this piece I wrote last year about the gendering of drinking, and after reading it I decided to check on Whiskey Catholic, the blog I mentioned in that post.

I want to like Whiskey Catholic. They offer great reviews, they seem supremely knowledgeable, and they write with the jolliness you find in many of the best Catholic writers.

Funny coincidence: the day I checked in, Whiskey Catholic’s most recent post was “Man Skills: Making a Table.” The first line reads: “There’s nothing more romantic than making something for a woman using your own two hands, especially if that something ends up looking better than what you could buy at a department store.”

(I’ve got something to say about the manliness of table-making, but I’ll save that for a follow-up post.)

Anyway, as I flipped through Whiskey Catholic’s posts, I started to think that Robert Christian might be right to say that the Catholic Church has a drinking problem. Don’t get me wrong—I don’t agree that the problem is the one Christian diagnoses. “While engaging in interfaith dialogue,” Christian complains, “the vast majority of thoughtful, virtuous young people I have met from other faiths have been teetotalers (those who abstain from alcohol entirely), while I have witnessed many of my fellow devout Catholics, who are otherwise morally serious, acting foolishly due to their consumption of alcohol.”

I flatly disagree with Christian that the Church should encourage teetotaling. Obviously.

No, for me, the real problem comes when the Church’s insistence on strict complementarianism gets all mashed-up with its love of drinking. What Crouch identifies in the Woodford ads is just a lazy failure to see beyond the gender binary. But in the hands of the writers at Whiskey Catholic, gendered drinking becomes something much worse: dogma.

In other words, for these writers, drinking, which should be liberating, is about reinforcing order. Where drinking could be seen as a way of breaking down divisions and building community, instead it becomes a means of building divisions and excluding others.

Take the “Whiskey Men” designation that Whiskey Catholic bestows on “men who lived fascinating and fruitful lives.” The honor, I guess, is meant as a sort of “Most-Interesting-Man-in-the-World” award, and Whiskey Catholic does write up some amazing stories, like this oneabout the priest who was recently awarded the medal of honor. But the last group of menthey gave the award to was (ahem) the U.S. Bishops, including Charlotte Bishop Peter Jugis who (ahem) “defended the Catechism” after a talk by Sister Jane Laurel that (ahem) “included evidence drawn from scientific studies.” And also Bishop Paprocki for refusing communion to pro-choice senator Dick Durbin.

This was Bishop Paprocki’s second “Whiskey Man” award; the first time, Whiskey Catholic cheered him for defending (ahem) traditional marriage in a talk in which he apparently told those who disagree with him to become Protestants. Seems to me like only a lousy shepherd would tell his sheep to jump the fence for another pasture, but what do I know?

Or take their series on “The Catholic Gentleman,” in which posts on things like how to tie a bow-tie are interspersed with calls to confront relativism and to persevere in the face of the Supreme Court “giving its tacit endorsement to sodomy and the redefinition of union.”

Essentially, whenever they delve into human sexuality, the writers at Whiskey Catholic are no different from any Catholic Right writers or websites: they build on the same gender essentialism, peddle the same myth of moral decline, make the same self-protective claims that their opponents are irrational, or selfish, or just haven’t given their arguments enough thought.

For them, whiskey just serves this ideology. As Crouch writes about the Woodford ads, “Whiskey is about enacting particular rites of manhood, alone with other men and the ghosts of the manlier men of the past.” That’s almost word-for-word what Taylor Marshall said in his interview with Whiskey Catholic.

Which is disappointing because a proper (ahem) theology of the bottle would actuallychallenge the accepted Catholic dogma regarding human sexuality. As I’ve written before, that dogma is most often expressed in terms of an analogy with eating:

The idea is this: eating and sex both give us pleasure, but both have a vital purpose—nourishment, in the case of eating, and reproduction, in the case of sex. [Folks on the Catholic Right] argue that when we have deliberately non-procreative sex (sodomy, masturbation, contraceptive sex) we’re separating the pleasure of sex from its vital purpose. And this is as unnatural as separating the pleasure of eating from its nourishment—which, [they] say, would be like eating a great meal only to intentionally throw it up.

But drinking has a vital purpose, too—hydration—and drinking alcohol works against that. When we ingest liquor we harm ourselves in lots of ways, and open ourselves to all sorts of unnecessary and potentially catastrophic risks.

That makes no sense under the rubric used to condemn non-procreative sexual activities. It only makes sense if we think about Rowan Williams’ question in “The Body’s Grace”: “But if God made us for joy?”

In other words, it’s impossible to reconcile the puritan, instrumentalist sexual ethic of the Catholic Right with a hearty embrace of alcohol. The best Catholic writers know this, and that tension animates all of their writing on booze. That’s why Chesterton’s “Wine When it is Red” conflicts with the oversimplified Thomist reasoning that undergirds the current Catholic thinking on sex, and it’s why Percy’s “Bourbon, Neat” has more in common with “The Body’s Grace” than the “Theology of the Body.”

Misguided as he is, Robert Christian is absolutely right to question where drinking fits in the current Catholic cosmovision, and he’s right to oppose “GK Chesterton’s pugnacious writings” on alcohol to the teachings of the Church. He gets what the writers at Whiskey Catholic don’t: you have to choose your drinking or your dogmatism, your bottles or your certitude, your whiskey or your self-righteousness.

Saturday, August 17, 2013

Taylor Marshall on Drinking and Marijuana

At his blog, Thomistic scholar Taylor Marshall argues that smoking pot is immoral/unnatural because it’s analogous to drunkenness, which

dulls a man’s powers of reason and therefore is a sin. Marshall, who enjoys his single malt, says a little bit of drinking is fine, but there’s a line between

being “merry at heart” and being “drunk as a skunk.” And that line is where

drinking starts to diminish your rational capacities.

Nothing against weed, but since it’s not the thrust of this blog, I want to focus on the argument Marshall makes regarding alcohol.

Marshall writes:

Then he goes on, “Drunkenness is evil because it blurs and muddies our highest faculty – rationality. Think about it. When a person is drunk, he resorts to how animals act. Drunk people act irrationally.”

Here’s his first mistake. Drunk people don’t act like animals. True, animals aren’t rational, but their actions are almost always rationally explainable in relation to a few simple urges: self-preservation, reproduction, etc. Drunk people are, um, less predictable. Which is why the next morning for them sometimes looks like this:

G.K. Chesterton gets this. In “Wine When It Is Red,” Chesterton writes: “The real case against drunkenness is not that it calls up the beast, but that it calls up the Devil. It does not call up the beast, and if it did it would not matter much, as a rule; the beast is a harmless and rather amiable creature, as anybody can see by watching cattle.”

Cattle don’t generally wake up in hotel rooms with tigers and strippers and human babies.

Marshall's second mistake is thinking he can draw a bright line between being "merry" and being "drunk," and that that line comes with the diminishment of rationality. All drinking diminishes our capacity for reason--that's the deal you make when you slug back that shot. What Marshall really means is that proper drinking doesn't diminish our rationality too much.

Which is fine to say, but a difficult guide in practice. Especially since the act of drinking itself makes it harder to reason about whether or not the next drink is a good idea. After all, most people who end up "drunk" started out aiming to get "merry."

Besides, I think Marshall kind of misses the point. You can't drink well if you're always worried about drinking sensibly, because drinking well sometimes means letting go of being sensible.

Chesterton agrees. "Certainly," he writes, "the safest way to drink is to drink carelessly."

In a 1969 interview with the Paris Review, the poet Robert Graves said that "The academic never goes to sleep logically, he always stays awake. By doing so, he deprives himself of sleep. And he misses the whole thing, you see."

That's part of what Chesterton's getting at. Drinking, at its best, is a shrugging off of responsibility, of care, of the need for logic. That's the joy of a happy hour at the end of a workday, or of a few glasses of champagne at a wedding. It's a way of saying Let's be useless for a while.

And this is a good thing. Look again at Marshall's list of things that mark us as human: writing novels, painting images, traveling to the moon and back. Marshall's right, we wouldn't do those things if we were animals. But we also wouldn't do them if we were totally logical, if we only focused on doing what was useful or what made logical sense.

The trick is to do these things so that they call up the angels and not the devil. I'm not saying that's easy, or that there's no risk involved. "All the human things are more dangerous than anything that affects the beasts," says Chesterton. But when it comes to drinking (or anything useless) the risk is mixed up with the good. And what you can't do--what I think Marshall is trying to do--is seal off one from the other.

Nothing against weed, but since it’s not the thrust of this blog, I want to focus on the argument Marshall makes regarding alcohol.

Marshall writes:

Humans use logic. We are rational. We have an intellect. Humans play chess. Humans follow the rules of grammar. Humans build suspension bridges. Humans paint images. Humans travel to the moon and back. Humans write novels. This is what makes humans like God and the angels. Our logical, rational, intellect is the greatest gift that God granted our species.

Then he goes on, “Drunkenness is evil because it blurs and muddies our highest faculty – rationality. Think about it. When a person is drunk, he resorts to how animals act. Drunk people act irrationally.”

Here’s his first mistake. Drunk people don’t act like animals. True, animals aren’t rational, but their actions are almost always rationally explainable in relation to a few simple urges: self-preservation, reproduction, etc. Drunk people are, um, less predictable. Which is why the next morning for them sometimes looks like this:

G.K. Chesterton gets this. In “Wine When It Is Red,” Chesterton writes: “The real case against drunkenness is not that it calls up the beast, but that it calls up the Devil. It does not call up the beast, and if it did it would not matter much, as a rule; the beast is a harmless and rather amiable creature, as anybody can see by watching cattle.”

Cattle don’t generally wake up in hotel rooms with tigers and strippers and human babies.

Marshall's second mistake is thinking he can draw a bright line between being "merry" and being "drunk," and that that line comes with the diminishment of rationality. All drinking diminishes our capacity for reason--that's the deal you make when you slug back that shot. What Marshall really means is that proper drinking doesn't diminish our rationality too much.

Which is fine to say, but a difficult guide in practice. Especially since the act of drinking itself makes it harder to reason about whether or not the next drink is a good idea. After all, most people who end up "drunk" started out aiming to get "merry."

Besides, I think Marshall kind of misses the point. You can't drink well if you're always worried about drinking sensibly, because drinking well sometimes means letting go of being sensible.

Chesterton agrees. "Certainly," he writes, "the safest way to drink is to drink carelessly."

In a 1969 interview with the Paris Review, the poet Robert Graves said that "The academic never goes to sleep logically, he always stays awake. By doing so, he deprives himself of sleep. And he misses the whole thing, you see."

That's part of what Chesterton's getting at. Drinking, at its best, is a shrugging off of responsibility, of care, of the need for logic. That's the joy of a happy hour at the end of a workday, or of a few glasses of champagne at a wedding. It's a way of saying Let's be useless for a while.

And this is a good thing. Look again at Marshall's list of things that mark us as human: writing novels, painting images, traveling to the moon and back. Marshall's right, we wouldn't do those things if we were animals. But we also wouldn't do them if we were totally logical, if we only focused on doing what was useful or what made logical sense.

The trick is to do these things so that they call up the angels and not the devil. I'm not saying that's easy, or that there's no risk involved. "All the human things are more dangerous than anything that affects the beasts," says Chesterton. But when it comes to drinking (or anything useless) the risk is mixed up with the good. And what you can't do--what I think Marshall is trying to do--is seal off one from the other.

Saturday, July 13, 2013

The Vatican on Graham Greene

One of the writers who got me started on this blog is Graham Greene, who called the protagonist of The Power and the Glory, one of the 20th Century's best English-language meditations on faith, a "Whisky Priest".

What the hell is a Whisky Priest? What does that mean?

On the one hand, the answer is obvious ("It's a priest who likes whiskey, duh!"); but on the other it seems like there's a lot more to explore there. Why isn't he just called a drunk? Or a sinner? Is he just a no-good priest, or is there some virtue in his whiskeyness? Questions like that are part of what I'm essaying to answer at Theology of the Bottle.

So I have to share this article from The Atlantic on Graham Greene's dossier at the Vatican, which I read in hard copy years and years ago but just remembered and dug up for y'all.

It's not surprising that Rome's censors worried about Greene's "'Immoral' or married priests; the ambiguity with which the central figure refers to God and the doctrines of the faith; the conviction or the virtue attributed to Protestants and atheists”. Nor is it surprising that, according to the article's author, some Vatican authorities were "Defensive about their authority (which they desired to assert even as they doubted its efficacy), and incapable of grasping the conceptual problems posed by Greene's writing,…”

But the most interesting nugget from this report is a quick glimpse of the man who would become Pope (now Pope Emeritus) Benedict XVI. The Atlantic reports:

“The records of censorial investigations undertaken after the death of Leo XIII, in 1903, are in the archives of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, and are not available to be consulted by outside scholars. In February of last year I sought and obtained an audience with the Congregation's prefect, Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger. To my request that an exception be made to the rules, the reply was one word, uttered without hesitation: 'Ja'."

Thursday, May 9, 2013

Bourbon, Bad and Good

Walker Percy was a fascinating dude. The author of (in my opinion) the best New Orleans novel, 1961's The Moviegoer, and a key champion of John Kennedy Toole's A Confederacy of Dunces, Percy was both an existentialist and a self-proclaimed "bad Catholic." On top of all that, he was a drinking man, and his short essay "Bourbon, Neat" has become a sort of touchtone text for religious people trying to make sense of their own drinking.

Maybe because of that, "Bourbon, Neat" is one of the most misread essays in the American canon. I guess because he called himself a Catholic, people figure that "Bourbon, Neat" is Percy's attempt to find virtue in bourbon, to show how drinking can be safe, healthy, and ordered.

Take Michael Barruzini's "Walker Percy, Bourbon, and the Holy Ghost," published at First Things. Now, I don't want to be too hard on this essay, because it's a good piece of writing, and it calls attention to Percy's excellent piece of writing.

But damn if Barruzini doesn't miss Percy's point.

In Baruzzini’s analysis, bourbon is one way of

answering the existential question of how to be

in the world. “No, not in the sense of drowning sorrows in

alcoholic stupor,” Baruzzini writes, “but in recognizing that it is in concrete

things and acts that we are able to be in the world.” Man drinks

bourbon, Baruzzini argues, like an eagle flies or like a mole digs, “because

that is what you are, what you are good at, what you love.”

And he concludes: “[B]ourbon is for

Percy a way to be for a moment in the evening. Why might one take an evening

cocktail? Baser reasons are: an addiction to alcohol, or the desire to appear

sophisticated. Better reasons, according to Percy, are the aesthetic experience

of the drink itself—the appearance, the aroma, the taste, the cheering effect

of (moderate) ethanol on the brain. Another reason is that a drink incarnates

the evening; it marks the shift from the active workday to a reflective time at

home. One simply must choose a way to be at a five o’clock on a Wednesday

evening. Instead of surrendering to TV, Percy recommended making a proper

southern julep.”

We can put aside the objection that

Percy doesn’t recommend mint juleps

(the essay is called “Bourbon, Neat,” remember), and we can ignore the fact

that Percy advocates the opposite of savoring the “appearance, the aroma, the

taste” of bourbon. Those are confusing aspects of Percy’s essay—he does give a

recipe for mint juleps, and he does have a beautiful line about the “hot bosky

bite of Tennessee summertime.”

The bigger problem comes in with Baruzzini’s insertion

of the word “moderate” into that last paragraph.

Where does he get the idea that Percy's essay is about moderation? The drinkers in "Bourbon, Neat" are desperate, awkward, and unhappy:

they drink illegally, they drink irresponsibly, they drink whatever they can

get their hands on, from Coke bottles and hip flasks and home-rigged stills. He

writes of a bunch of teenaged boys so scared of girls that they hide in the bathroom during a school dance, swilling whiskey and wincing at its taste. He writes about turning to bourbon when he has no idea what to say on a date. And he writes of a julep party on Derby Day where “men fall face-down unconscious,

women wander in the woods disconsolate and amnesiac, full of thoughts of Kahlil

Gibran and the limberlost.”

But to hear Baruzzini tell it, Percy is advocating the stolid,

responsible pleasures of a cocktail made with good whiskey, taken from an

evening chair, maybe before going out into the backyard to toss the ball around

with the kids and, then, once they’re bathed and off to sleep, making stolid,

responsible love to the wife.

Percy’s ideal of whiskey drinking is far, far from that. It’s:

“William Faulkner, having finished Absalom, Absalom!, drained, written out, pissed-off, feeling himself over the edge and out of it, nowhere, but he goes somewhere, his favorite hunting place in the Delta wilderness of the Big Sunflower River and, still feeling bad with his hunting cronies and maybe even a little phony, which he was, what with him trying to pretend that he was one of them, a farmer, hunkered down in the cold and rain after the hunt, after honorable passing up the does and seeing no bucks, shivering and snot-nosed, takes out a flat pint of any Bourbon at all and flatfoots about a third of it. He shivers again but not from the cold.”

So "Bourbon, Neat" isn't about drinking to be yourself--it's about drinking to escape yourself.

Yeah, it can be, but Percy hates what he calls the "everydayness" of modern life. And so he celebrates drinking, even bad drinking with all of its risks, because those risks are what allow bourbon to lift us out of that everydayness. In other words, for Percy, drinking whiskey is man’s (or woman's) way of getting at the unfathomable, of launching himself into the wilderness of mystery. Even when he does it from his armchair.

Now, Barruzini is right that there's a religious aspect to all this. But he's wrong to look for it in the concept of vocation (doing what God calls you to do) rather than in the concept of grace. We don’t drink booze because it’s good for us, Percy is telling us. We drink it because it’s not. And somehow, that’s good.

That “somehow” is grace.

Booze is grace.

Can I get an amen?

(photo of Walker Percy courtesy Linda Faust/Winston Riley Productions)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)